Let’s talk sustainable ceramic practices

I started my obsession with all things pottery 3 years ago. My first wheel throwing lesson had me hooked! I believe it is the mindful spinning of the wheel, the tactile earthiness of the clay and the creation of something handmade, that continues to fuel this passion. It is my therapy!

I made some pretty awful pieces in my beginner days. (Sometimes still do) Pieces that I was desperate to glaze and fire because having something created with my hands was such an achievement.

My house (and the homes of friends) is filled with weird looking ceramics that look a bit like a bowl or maybe something that can pass as a cup…. Lol

As a keen advocate of zero waste and sustainability, it made sense to look deeper into my ceramic practice and find ways to lesson my stress on the environment. Pottery has experienced a revival in the last few years and with it an abundance of unwanted fired pieces, broken or left gathering dust on shelves all over the world. Where do they go from here? Notably landfill.

This bothered me so much that I began my quest to find out how I could do something about it.

There are a few individuals, worldwide, creating sustainable or circular ceramics.

Let’s take a look at some of those practices;

· Single firing – skipping the bisque fired stage straight to glaze firing.

· Reclaiming clay – an easy practice all potters can and should be doing. This practice involves collecting all scraps of clay from throwing, trimming or leatherhard pieces not fit for firing, mixing it into a slurry and drying on a plaster slab.

· Making glazes from studio glaze waste or using plants and natural pigments.

· Grinding fired pieces into smaller or a very fine powder and adding into clay. (This excites me a little too much…lol)

· Discernment over pieces made before firing… does it make the cut or should it be reclaimed? Do I really need ANOTHER bowl?!?!

Ask any potter and they’ll tell you it’s the process that satisfies them most. Yes, excitement ensues when a piece emerges from the kiln and is something to behold. But the most therapeutic part is the process of putting your hands in the cold, wet slop that is clay.

We are living such overindulgent times that we often negate to stop and think about what we are buying, making, or creating, how it is made, where the materials are sourced and whether it will impact the environment, short or long term.

The research is clear, art and creative pursuits are essential for our wellbeing and more and more individuals are recognising this. But this comes at a cost to our precious planet with such an increase in waste, the mining of resources and the creation of chemical substitutes.

So here’s my challenge to you, can you make at least one change in your ceramic practice that considers your natural environment and the planet?

Made from waste

Feel free to share with me ways in which you are already practicing sustainably. Sharing our knowledge means a wider impact.

Until next time

Cate x

What is Art Therapy and does it help heal trauma?

Art therapy: quite simply “is not a dusty relic hung in a museum but a living work in progress” Vick

Art therapy is gaining traction as an important resource for healing trauma and whilst this paper concentrates on traumatised youth, the evidence for adults is comparatively similar. My background is in paediatric nursing and therefore I have a strong pull towards helping children. In my opinion, many of us with unhealed childhood wounds are externally projecting our inner child’s unmet needs or traumatic experiences in our everyday relationships, not only with others, but also, with ourselves. So, I think it is important to understand how trauma affects children, then we go some way to understanding the how and why of our adult unhealthy behaviour. Trauma is a complex subject and this paper will provide a snippet of what happens to the body in relation to traumatic events and how a resource such as Art Therapy can help heal those wounds.

Art therapy aims to act as a communication tool for the unconscious, bringing forth fragmented memories, feelings, thoughts, and emotions that are incapable of being verbalised. Wallace (2015) suggests art therapy utilises the individual’s creative aspects to engage with emotional, psychological/or physical issues, providing opportunities to unblock and reform old habits and ideas. Furthermore, the mere act of creating art can bring forth calmness, healing of deep wounds, new perspectives and bringing one into the present, deepening relationship with self that allows for self-growth, awareness, and self-understanding (Wallace, 2015; Edwards, 2014). Edwards (2014) posits the physical permanence of shapes and forms created through art making act as lasting records in which the client can continue to reflect upon, providing emotional growth and a better understanding of one’s experience of the world.

Today, art therapy is utilised with varying approaches and foundational theories and is inextricably linked with the discoveries of neuroscience. Gussak & Rosal (2016) agree that advances in neuroscience help to explain the mind/body connection and allow contemporary art therapists to utilise this knowledge in their interventions with clients. Gussak & Rosal (2016) also suggest that art therapists should have an openness to varied theoretical perspectives, and whilst art is at the heart of art therapy, a deep understanding of human psychology and how it alters in relation to life experiences is imperative (Rubin, 2016). Through the very creation of art making, individuals are able to find and understand the significance of these experiences. Art therapy: quite simply “is not a dusty relic hung in a museum but a living work in progress” (Vick, 2003 pg13).

Trauma is the result from either a singular experience or multiple events that are unbearable, intolerable, and significantly impact an individual’s psychology, emotionally and somatically.

Before there can be exploration into how art therapy may benefit trauma, it is important to define trauma, and the neurobiological and physiological responses. Trauma, especially in regard to youth, is a broad and complex subject, therefore for the purposes of this , it will be described in ways that may provide the reader with a basic understanding of the effects of trauma for children and how such creative therapies as art may be of benefit in helping children heal and experience more wholesome and joyful lives.

What is trauma

The multifarious definitions of trauma make it difficult to provide a succinct clarification on the meaning, however, consensus amongst some authors suggest trauma is the result from either a singular experience or multiple events that are unbearable, intolerable, and significantly impact an individual’s psychology, emotionally and somatically (Malchiodi, 2020; van der Kolk, 2014; Malchiodi & Perry, 2008; Talwar, 2007). Furthermore, trauma is noted to be the consequence of a perceived threat that overwhelms the individual’s internal coping mechanisms, resulting in an inability to respond (Werbalowsky, 2019). The impacts of such events will be determined by the individual’s capacity for resilience and affect regulation (Talwar, 2007). Therefore, it is not necessarily the event or experience itself but rather one’s internalised response to such events that impact the ensuing complex sequelae. Malchiodi & Perry (2008) extend further in suggesting those children who do not have adequate familial and community support and experiencing socioeconomic instability and political upheaval are at higher risk of long-term trauma disorders. Traumatic responses in children are sadly commonplace and may result from events such as but not limited to; divorce, death of a loved one, relocation, foster care, medical illness, bullying, domestic/community violence, physical/sexual/emotional abuse, war, or terrorism (Malchiodi, 2008; van Westerhenen et al, 2017; van der Kolk, 2014). Moreover, instances where a child’s needs are not met, through neglect or abandonment, can also be a trigger for a traumatic experience. Meshcheyakova (2012) extrapolates that trauma originating from the interruption or non-existence of nurturing attachment relationships can result in significant developmental issues with children who experience this type of neglect and abandonment.

It is not necessarily the event or experience itself but rather one’s internalised response to such events that impact the ensuing complex sequelae.

Neurobiology and physiological effects of trauma

Developments of intervention and treatment protocols require a deeper understanding of what occurs in the mind and body as a result of traumatic experiences. Malchiodi (2008) suggests the “compartmentalised, evidence-based practice dominated by reductionist medical models” are doing a dis-service to traumatised children and there is a greater requirement to provide therapeutic experiences that align with the true understanding of the effects of trauma. Childhood in and of itself is a vulnerable period and the economic, creative, and productive costs of childhood trauma are fracturing their ability to live meaningful lives (Malchiodi, 2008). Furthermore, traumatic experiences can have short- or long-term effects on the emotional, physical, psychological, and spiritual aspects of an individual and can present in unpredictable, pervasive, and multifaceted ways (Malchiodi, 2020; van der Kolk, 2007).

With no access to processing information, explicit memory storage or language, dissociation occurs, and memories become sensory fragments trapped in the body as intense emotional sensations and images

Trauma directly effects the central nervous system, in particular the limbic system whose responsibility is helping us survive (Malchiodi, 2008). The limbic system or emotional brain controls feelings, needs and desire and storage of implicit memory (Malchiodi, 2008). The neocortex is responsible for language, thinking, reasoning and storage of explicit memory. It is understood that during an experience that an individual perceives as threatening, the limbic system goes into disarray, rather than expend the energy created by a hyperarousal (flee or fight) or hypo arousal (freeze, fain) state, it becomes trapped in the nervous system and the neocortex shuts down (Malchiodi, 2008). With no access to processing information, explicit memory storage or language, dissociation occurs, and memories become sensory fragments trapped in the body as intense emotional sensations and images (van der Kolk et al., 1985; Sigal,2021). This storage of illicit memory and failure to integrate these sensory imprints into explicit memory keeps traumatised individuals in an increased hyper-vigilant state (Talwar, 2007). The impact of the inability to make conscious reasoning of such experiences therefore lends itself to the challenges and difficulties traumatised individuals endure. In the case with young people, who may be developmentally disadvantaged in emotional regulation or lack the primary relationships to help achieve regulation, they can lose their sense of control and stability, experience the external world as unsafe and become helpless (van der Kolk, 2005). Sensory responses from smells, sounds, images, touch, or taste can trigger the unconscious traumatic memories and the individual’s nervous system responds into the same heightened physiological arousal as if the original event is happening in the present (Talwar,2007). With an inability to regulate these emotional responses and a development of habitual responses, children may present with but not limited to; outbursts of anger and violence, withdrawal, avoidance, depression, anxiety, attachment issues, distrust of others and self-harming (van der Kolk, 2005; Malchiodi, 2008). Moreover, they may go on to develop a lack of sense of self, inability to modulate affect and impulse control, uncertainties with the predictabilities and reliabilities of others, social isolation, loneliness, problems with future relationships and intimacy, which may all have further implications for criminal and addictive activities, suicide or becoming the perpetrators of abuse themselves (van der Kolk, 2005; van Westrhenen et al, 2017).

Benefits & goals of Art therapy for traumatised youth

Art therapy strengthens healthy coping skills and resilience, especially in situations where verbal psychotherapy has failed.

Understanding how the body reacts to traumatic experiences, the implicit storage of memory, trapped emotions and how art therapy is evidenced to give rise to the unconscious, it clearly makes sense that art therapy as a somatic intervention to healing trauma is a vital and much needed resource. Van Westrhenen et al (2017) & Talwar (2007) concur, that while establishing protocols for treating traumatised children is arduous, there remains evidence that art therapy strengthens healthy coping skills and resilience, especially in situations where verbal psychotherapy has failed.

Through the utilisation of ‘art in therapy’, clients are encouraged to describe their artwork, telling of their story, associating meaning with their experiences, thus integrating implicit and explicit memory, verbal, and nonverbal processes

Art therapy has been shown to support the connections between body- mind and creativity, help reduce the acute stress responses in children with Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) (Talwar, 2007). Talwar (2007) and van Westrhenen et al., (2017) also reiterate art therapy’s achievements in tapping into the nonverbal domain of imagery, overcoming language barriers and the possibility of integrating implicit and explicit memory to resolve re-experiencing of memory. Through the utilisation of ‘art in therapy’, clients are encouraged to describe their artwork, telling of their story, associating meaning with their experiences, thus integrating implicit and explicit memory, verbal, and nonverbal processes (Talwar,2007). Van Westrhenen et al., (2017) propose the use of art therapy in providing a safe space to stimulate the sensory and cognitive processing of traumatic memories with a goal to enhance the psychological wellbeing of the individual and the strengthening of positive development. Additionally, drawing and painting can elicit projections of situations or emotions as separate from the person, giving rise to less resistance (van Westrhenen et al, 2017)

Art therapy allows for supporting the re-connection to the body in a safe way, by utilising tasks that engage the child in feeling and naming sensations within their body during and after the process

Malchiodi (2008) augments that drawing can decrease anxiety, increase the reorganisation and retrieval of the trauma narrative. The utilisation of art therapy group work serving as a foundation for regaining trust, building healthy relationships, prosocial behaviour, and connections, and allowing the child to know they are not alone, helps create positive outcomes for traumatised youth (van Westrhenen et al, 2017; DeMott, 2017). Art therapy allows for supporting the re-connection to the body in a safe way, by utilising tasks that engage the child in feeling and naming sensations within their body during and after the process (Sigal, 2021).

In essence, Art Therapy can help heal from traumatic experiences by tapping into the unconscious and bridging the path between implicit and explicit memory, allowing us to make sense of, have compassion for and integrate the fragmented parts of our wholeness.

Want to experience the powerful modality of Art Therapy? Please contact me to book a session.

With love and compassion

Cate x

References

ANZACATA (March 20 2022). What is art therapy and creative art therapies? https://anzacata.org

American Art Therapy Association [AATA] (n.d.) About Art Therapy https://arttherapy.org/about-art-therapy/

Bowen-Salter, H., Whitehorn, A., Pritchard, R., Kernot, J., Baker, A., Posselt, M., Price, E., Jordan-Hall, J., & Boshoff, K. (2021). Towards a description of the elements of art therapy practice for trauma: A systematic review. International Journal of Art Therapy, 27(1), 3-16. https://doi.org/10.1080/17454832.2021.1957959

British Association of Art Therapists (n.d.) What is Art Therapy? https://www.baat.org/About-Art-Therapy

Edwards, D. (2014). Art therapy (2nd ed.). SAGE.

Gussak, D. E., & Rosal, M. L. (2016). The Wiley handbook of art therapy. John Wiley & Sons.

Junge, M. (2016) In Gussak, D., Rosal, M.L. (Ed.) Wiley Handbook of Art Therapy. John Wiley & Sons.

Malchiodi, C. A. (2008). Creative interventions with traumatized children. Guilford Press.

Malchiodi, C. A. (2011). Handbook of art therapy (2nd ed.). Guilford Press.

Malchiodi, C. A. (2020). Trauma and expressive arts therapy: Brain, body, and imagination in the healing process. Guilford Publications.

Meshcheryakova, K. (2012). Art therapy with orphaned children: Dynamics of early relational trauma and repetition compulsion. Art Therapy, 29(2), 50-59. https://doi.org/10.1080/07421656.2012.683749

Meyer DeMott, M. A., Jakobsen, M., Wentzel-Larsen, T., & Heir, T. (2017). A controlled early group intervention study for unaccompanied minors: Can expressive arts alleviate symptoms of trauma and enhance life satisfaction? Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, 58(6), 510-518. https://doi.org/10.1111/sjop.12395

Rubin, J. A. (2016). Approaches to art therapy: Theory and technique (3rd ed.). Routledge.

Sigal, N. (2021). Dual perspectives on art therapy and EMDR for the treatment of complex childhood trauma. International Journal of Art Therapy, 26(1-2), 37-46. https://doi.org/10.1080/17454832.2021.1906288

Thomas, B. S., & Johnson, P. (2007). Empowering children through art and expression: Culturally sensitive ways of healing trauma and grief. Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

Taçon, P.S.C., (2019). Connecting to the ancestors: Why rock art is important for Indigenous Australians and their well-being. Rock Art Research. 36(1) 5-14.

Talwar, S. (2007). Accessing traumatic memory through art making: An art therapy trauma protocol (ATTP). The Arts in Psychotherapy, 34(1), 22-35. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aip.2006.09.001

Van der Kolk, B., Greenberg, M., Boyd, H., & Krystal, J. (1985). Inescapable shock, neurotransmitters, and addiction to trauma: Toward a psychobiology of post-traumatic stress. Biological Psychiatry, 20(3), 314-325. https://doi.org/10.1016/0006-3223(85)90061-7

Van der Kolk, B. A. (2007). The developmental impact of childhood trauma. Understanding Trauma, 224-241. https://doi.org/10.1017/cbo9780511500008.016

Van der Kolk, B. (2014). The body keeps the score: Mind, brain and body in the transformation of trauma. Penguin UK.

Van Westrhenen, N., Fritz, E., Oosthuizen, H., Lemont, S., Vermeer, A., & Kleber, R. J. (2017). Creative arts in psychotherapy treatment protocol for children after trauma. The Arts in Psychotherapy, 54, 128-135. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aip.2017.04.013

Vick, R. (2003). A brief history of art therapy. In C. A. Malchiodi (Ed.) Handbook of art therapy (pp. 5–15). New York: Guilford Press.

Wallace, K. O. (2015). There is no need to talk about this: Poetic inquiry from the art therapy studio. Springer.

Werbalowsky, A. (2019). Breathing life into life: A literature review supporting body-based interventions in treatment of trauma. Expressive Therapies Capstone Theses. 161.

Neuroaesthetics - Art’s powerful influence on our well-being

Ever wondered why or how engaging in creative activities makes you feel so good?

Now that science has finally caught up to what all of us creatives/artists already know, we have some scientific evidence. And a new field of science… ‘neuroaesthetics’.

Neuroaesthetics is the name applied to the study of how the brain interprets creative activities and changes behaviour, feelings, and bodily sensations.

Art is now recognisied as an essential component to human well-being.

Ever wondered why or how engaging in creative activities makes you feel so good?

Now that science has finally caught up to what all of us creatives/artists already know, we have some scientific evidence. And a new field of science… ‘neuroaesthetics’.

Neuroaesthetics is the name applied to the study of how the brain interprets creative activities and changes behaviour, feelings, and bodily sensations.

Art is now recognisied as an essential component to human well-being.

It’s not an entirely new scientific field, apparently the emergence began in the late 1990’s and the term first coined by Neuroscientist Semir Zeki, according to Susan Magsamen – founder of International Arts + Mind Lab Center for Applied Neuroa

esthetics. Magsamen also reiterates the arts have shown to have profound changes not only psychologically and physiologically but also spiritually. Having seen the emotional and spiritual transformations of those in end-of-life stages, I would agree.

Why does understanding how the arts transform our being become important? Well, it helps us therapeutic arts practitioners find the best activities to support specific conditions that are evidence based. As Magsamen articulates it enables us to fine tune specialized programs that are better suited for healing through the arts.

Art therapists have been doing this for decades with little scientific data to back up what they see occur in the art therapy room with their clients. If we step back in time and I mean a long time ago, the evidence is clear to the use of art for emotional expression.

What we today coin art has its roots in prehistoric times. Research into early human life has discovered that therapeutic rituals took place amongst indigenous tribes, through sand and cave painting, sculpture, dance, and storytelling and can be seen as precursors to the understanding of art therapy today (Junge, 2016; Malchoidi, 2008; Rubin, 2009). Early Indigenous Australian rock art has strong underpinning connections to wellbeing in our First Nations people’s. Whilst this form of art had benefits to the indigenous communities at the time, it remains a form of strong connections to history and culture for today’s indigenous people. Their sense of emotional, psychological, and spiritual wellbeing is highly correlative with their connections to country, ancestors, their culture, and stories. Therefore, this ancient form of art making has significant impact on the wellbeing of today’s indigenous people. Taçon (2019) concurs, a positive sense of cultural and personal wellness originates from strong cultural identity that is underpinned by such connections. Their lore’s, language, philosophies, and ways of living are etched in those early art creations, that keep their culture alive and strong, powerfully linking country, past and people and profoundly impacting on the wellbeing of current First Nations generations. Ancient cultures worldwide have used art, dance, storytelling to help face challenges, make sense of their world and their relationships (Vick, 2003). Despite these very early observations of the importance of creative art making for humans, it has taken significant time to emerge into current day therapy and gain the credibility it deserves.

Creative arts encompass a wide range of activities; it’s not just what we know to be art, i.e painting, drawing etc, it is also movement, drama, dance, music, cooking, and writing. When our expression comes from deep within the psyche or the soul it reveals the truth, it shifts the energy and has the capacity to heal wounds. When we are switching our brain activity from left side intellect, reasoning, and analytical behaviour to the right-side activities we are allowing our intuition, spontaneity, and imagination to be seen and heard.

Curiosity, surprise, and wonder are evoked in the art maker or art lover and Magsamen again reiterates that these experiences are fundamental to the well-being of, not only, the individual, but also, on the collective human experience.

Neuroscience has awarded us the opportunity to understand just how the brain’s neurons can change and adapt and it has been noted that these neural pathways will grow dramatically when we put ourselves in an environment that is not only new but also safe and sensorial. Current research is showing us in great detail how our senses are experiencing aesthetic experiences, transporting those to the brain which allows identification of measurable biomarkers. Whether we know it or not, the body is experiencing the arts in profound ways.

Through monitoring MRI images of people engaging in art activities or even admiring artworks, researchers have found an activation of the reward centre lights up, subsequently releases feel-good hormones such as dopamine, oxytocin, and serotonin. The result, sensations of pleasure and affirmative emotions.

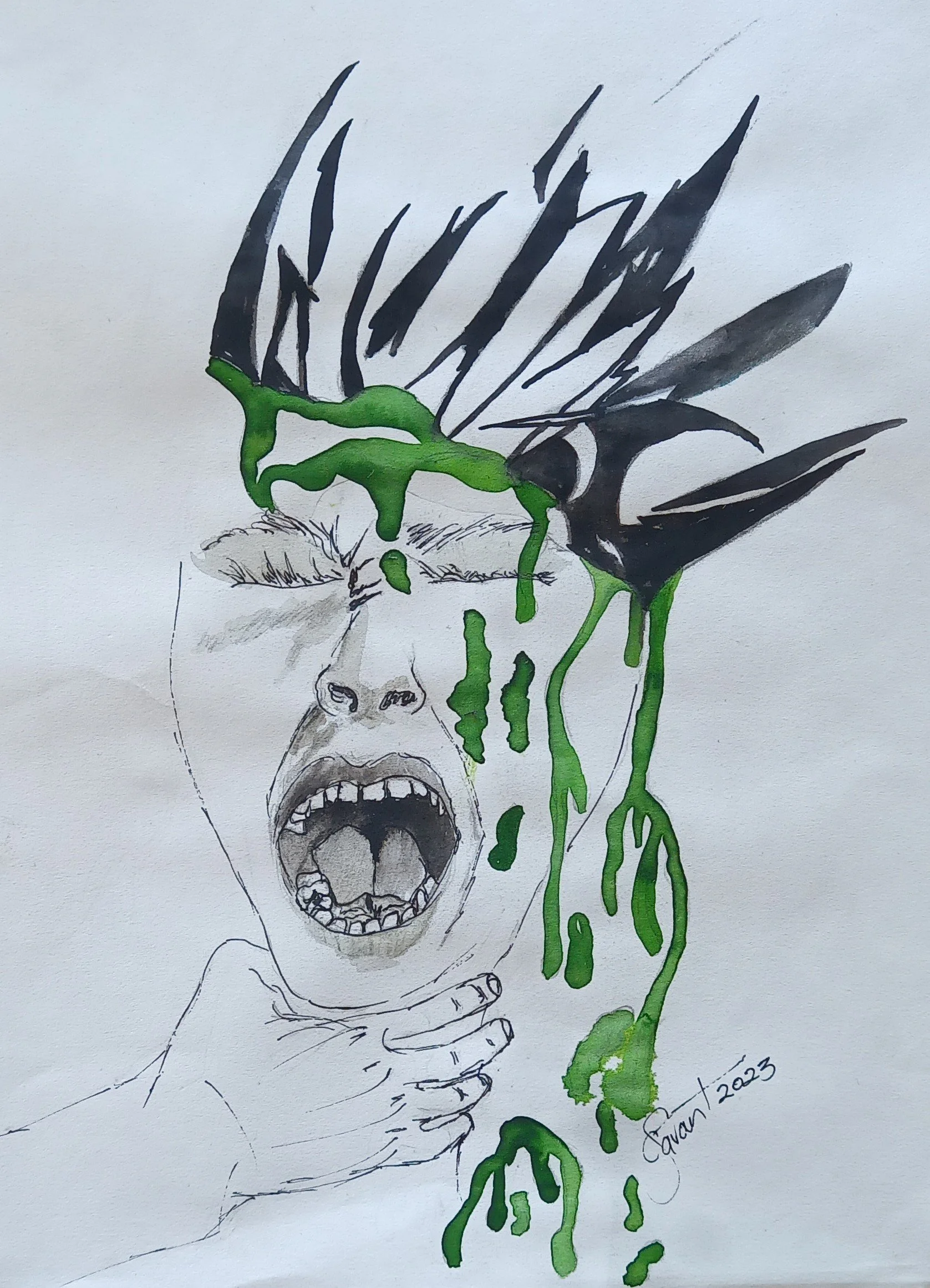

Can you think to a time when you are experiencing chaos, how does this make your body feel?

Author’s perception of her brain on stress and chaos.

Now put yourself in a creative environment where there is no judgement, expectation, or rules, only acceptance, freedom, flow, and connection. How does the body respond? I would dare say you notice your shoulders drop, your jaw relaxes, the breath becomes easier, the body feels more flexible and open, and an overall sense of peace is felt.

Does your brain feel a sense of relief?

I know mine does.

Author’s visual perception of her brain on art. Peace and contentment.

Healing from life’s challenges and traumatic experiences can often feel heavy, fearful, and never ending as the elusive search for peace and contentment can make our brain tired. Thinking our way through healing is exhausting and often doesn’t get to the healing space…. the core root of our issues. It doesn’t have to be hard or exhausting, we need to find the right activity that works for us. That might be art in therapy or art as therapy, maybe movement is your thing. Trauma informed yoga and somatic movement are gentle but oh so powerful. Maybe it’s getting your hands dirty with some clay, this one has become an obsession for me (clearly have a lot more healing to do…). Cooking and gardening are also creative pursuits that connect you with the earth and have the added benefit of helping you ground. Writing… poetry, fiction, non-fiction, children’s stories. Stepping away from the voice of judgement and expectation and being free to allow buried creativity to emerge has so much potential to allow us to thrive.

We are a society high on anxiety, depression, suicidality and chronic health problems and the old conventional allopathic ways are not working (I’m not sure they ever did in all honesty).

Whilst we are hard wired for negativity, according to Brené Brown and arrive in this life with ancestral baggage seeping out of our DNA, there are solutions to feeling better and I strongly believe the answers lie within the creative fields. Good news is that our DNA not only carries the murky stuff but according to Magsamen, “aesthetic experiences and the arts – are hard-wired in all of us”.

And the excellent part, research suggests that the maker does not require any ounce of proficiency to benefit from creative pursuits.

So, let’s get out of our left-brain comparative, reasoning brain that shouts, ‘I’m not artistic or creative’ and get our hands and bodies moving and allow the emergence of the creative soul within. It’s time to be free, to feel better and to thrive.

Resources

Your Brain on Art: The Case for Neuroaesthetics. Susan Magsamen. 2019. www.ncbi.nim.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC70755

Junge, M. (2016) In Gussak, D., Rosal, M.L. (Ed.) Wiley Handbook of Art Therapy. John Wiley & Sons.

Malchiodi, C. A. (2008). Creative interventions with traumatized children. Guilford Press.

Rubin, J. A. (2016). Approaches to art therapy: Theory and technique (3rd ed.). Routledge.

Taçon, P.S.C., (2019). Connecting to the ancestors: Why rock art is important for Indigenous Australians and their well-being. Rock Art Research. 36(1) 5-14.

Vick, R. (2003). A brief history of art therapy. In C. A. Malchiodi (Ed.) Handbook of art therapy (pp. 5–15). New York: Guilford Press.